A polynomial in one variable is a combination of powers of

. For example,

or

are polynomials, while

is not a polynomial, since the term

cannot be written as powers of

(at least as a finite combination of such powers).

A root of a polynomial is a number

for which

. With the polynomial

above,

is a root since

. When the highest power of

in a polynomial (called the degree of the polynomial) is

, we all the polynomial a quadric (in the literature it seems that quadric is used as a noun while quadratic is used as an adjective). You may recall the quadratic formula that produces the roots of such polynomials: for a quadratic

,

the roots are

.

Let’s consider two quadratic polynomials and

. Using the quadratic formula, the roots of

are

and the roots of are

.

I did not approximate the roots of , because they are not real numbers. The

is not a real number; it is called a complex or imaginary number. To see that it is not real, let’s suppose it is and see what happens.

Let’s say for some real number

. Then squaring both sides, we get

. If you square a positive number, the result is positive. If you square a negative number, the result is also positive. Yet we have

, so we have arrived at a contradiction. Therefore,

cannot be a real number.

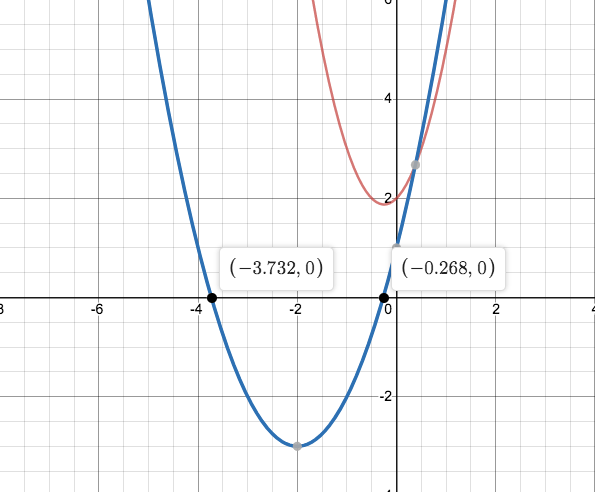

We can see this on the graphs of the two functions:

The red graph is and the blue graph is

. We see that the blue graph crosses the

-axis exactly at the roots we found, and that the red graph never touches the

-axis. When a root does cross the

-axis, or, equivalently, is not complex, we say it is a real root. The rest of the post focuses on real roots.

One of the oldest problems in mathematics is how to find roots of polynomials. Indeed, there used to be competitions with big monetary prizes for who could compute roots the fastest, and if you found a general formula for the roots (like the quadratic formula), you became famous in the math world. There are actually formulas when the degree is , or

, and there are incredibly wonderful proofs from different branches of mathematics that show that no formula for degree

can exist.

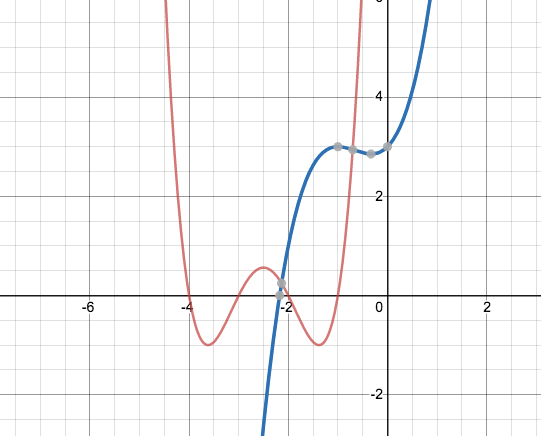

What I now describe is not a method to find real roots, but rather a condition which says when real roots do not exist. Let’s look at two more polynomials with their graphs.

The red graph is the graph of

and the blue graph is the graph of

The numbers in front of each power of are called coefficients. The sequence of coefficients of

are

, the the sequence of coefficients of

are

.

Notice that the red graph crosses the -axis four times, and the blue graph only crosses the

-axis once. The degree of

is

, and the degree of

is

. It is not hard to show (or see) that a polynomial of degree

cannot have more than

roots. Therefore, all roots of

are real, and there are some non-real roots of

(the blue graph crosses the

-axis like a straight line, which means the roots has multiplicity one, which I won’t go through the trouble of defining – but this is why the latter statement is true).

Now here is the fascinating fact: I could have told you that had some non-real roots within 2 seconds of looking at the equation! This fact follows solely from the coefficients of

. Think of the sequence of coefficients by comparing neighbors:

There are too many inequality switches for this polynomial to have all real roots. Earlier we saw that the quadric had non-real roots too, and notice that

.

Compare this to the sequences of coefficients of :

.

This is an example of a unimodal sequence of numbers; more generally, a unimodal sequence of numbers increases up to a peak (in this case, ), and if the sequence begins to fall, it never rises again.

We can now state the Main Theorem:

Theorem: If the sequence of coefficients of a polynomial is not unimodal, the the polynomial has non-real roots. Said differently, if all the roots of a polynomial are real, then the sequence of coefficients is a unimodal sequence.

The rest of this post gets pretty formal.

Before we start, let’s define one more thing: the derivative. This term is essential in calculus, and instead of going in depth, I’ll just say what it is for a polynomial: the derivative of a polynomial is computed term-wise by taking

and turning it into

. We write

for the final result. For example, for

we get

.

If we did this again, we would call it , and so on. You can easily check that

, and

for

.

The Main Theorem with Proof

First we formalize a term mentioned above and then re-state the Main Theorem. Let be a sequence of positive integers. If there is some

for which

then we say that the sequence is unimodal.

Theorem: Let be a sequence of positive integers. If all roots of the polynomial

are real, then is a unimodal sequence.

This theorem is proven by the following three steps.

Proposition 1: If all roots of

are real, then for all

.

Corollary 2: If all roots of

are real, then for all

.

Lemma 3: If are positive integers and

for all

, then the sequence is unimodal.

Proof of Lemma 3: Suppose . We need to show that

. To show

, since these are positive, it suffices to show

. But

, so

.

Applying this argument inductively, we obtain the result.

Proof of Corollary 2: As the name suggests, this proof depends on Proposition 1, which we are proving next. Assuming its truth, we define a new sequence by setting

.

Then

has all real roots, so for all

by Proposition 1. It is easily checked that this implies

for all

.

Proof of Proposition 1: An application of Rolle’s Theorem is that if a polynomial has all real zeros, then so does all of its derivatives. Then

has all real zeros, which implies

has all real zeros, which implies

has all real zeros. This last polynomial is the quadric

,

which has zeros only if the discriminant is nonnegative; i.e.,

.

I learned of these proofs from Stanley in this paper.